Snapshot

- WalkTransit could well be an extensive, safe and innovative public transport system for every neighbourhood in the cities.

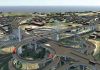

The idea of a pod taxi has been doing the rounds in India. This was initially mooted by the Ministry of Road Transport for a network of driverless vehicles to connect New Delhi with Manesar or Gurugram, in Haryana, and has been picked up also by the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) covering six lines in the city.

Developed by Metrino Personal Rapid Transit, the system involves “small, fully automatic, driverless vehicles called pods” that would travel suspended under an overhead network which itself would be laid over the median of a highway stretch.

The pods can seat a maximum of five people at a time for individual trips at an average speed of 50 km per hour. The company claims the cost of construction is 50 times lesser than for an underground metro – or about Rs 50 crore per kilometre – with a maximum carrying capacity of 6,000 passengers per direction per hour compared to 3,000 for buses and 40,000 for the metro.

At this cost, it would still amount to Rs 2,500 crore (almost $410 million) for a 50 km coverage in any Indian city. Cheaper than a metro, but could we better this?

WalkTransit: Travelators as inexpensive public transport

Imagine we had something similar to the Metrino, an overhead system running above the road medians which could perform much the same task of transporting people at an order-of-magnitude lesser cost of construction – say, Rs 10 crore per kilometre. And this system could deliver not one but multiple benefits.

Too good to be true?

We are talking of a moving walkway or travelator – a “WalkTransit”.

Far, far less expensive to build, no complicated “yet-to-prove” technologies, no urban land to procure, comfortable and aesthetic to encourage people to use it, highly safe, and one that integrates very well with existing transportation infrastructure.

How good would this be?

A short history

From an engineering perspective, the concept is very old – the first travelator was installed at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, followed by one at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900.

The Beeler Organization, a New York consulting company, proposed a continuous transit system for Atlanta in 1924 that involved a linear induction motor. In 1954, Jersey City in the United States of America deployed the first commercial moving walkway inside a railway station, and the first one inside an airport was installed in Dallas in 1958.

These were short distance, slow, travelators that can still be seen at many airports around the world.

In the 1970s, Gabriel Bouladon and Paul Zuppiger of Dunlop developed the Speedaway, a high-speed prototype that was demonstrated at the Battelle Institute in Geneva. Their design achieved a maximum speed of 15 km per hour and also had a unique differential embarking/disembarking section – a wide walkway, moving at a speed of about 4 km per hour and a narrower, high speed, transport section that could achieve the maximum stated speeds.

The Speedaway never achieved commercial production, and many other attempts followed – the TRAX developed by Dassault in the 1980s and installed at the Paris Invalides metro station; the Loderway Moving Walkway installed at the Flinders Street Station in Melbourne, Australia in the 1990s; and the experimental high-speed installed at the Montparnasse-Bienvenue metro station in Paris in 2002.

The last of these travelled at a maximum speed of 6 km per hour (although it could travel faster at 12 km per hour but found that people were losing their balance at that speed).

A different design heuristic for Indian cities

Keeping in view the possible constraints (usage by senior citizens and children; maximum use in local neighborhood areas and not for long-distance commuting; and as a compelling and competitive complementary alternative, but not a substitute, to existing metro, city bus and private vehicles that would likely need some enticement in the form of cost, comfort and a pleasant traveling experience) this old idea of travelators could be improved upon to provide Indian urban areas with an inexpensive transport.

This could even be the magic bullet for Prime Minister Modi’s oft-discussed smart city transit planning.

The urban WalkTransit could be broad and, as with airport travelators, have an immobile section on one-half for individuals who wish to stand rather than walk with handrail support, and the other moving half for people who wish to walk on it and thus get some exercise. The whole thing could be enclosed in an air conditioned tubular or oblong glass structure to provide passengers with a pleasant and non-polluting experience.

The “stations” could be much smaller and sparse with covered escalators and elevators to both sides of the road.

The important thing to note is that travelator designs in Europe that attempted at a fast public transit have generally failed for reasons of complexity and safety.

Many of them had a railway station design heuristic that sought to separate much slower moving traffic for people wanting to get off at a station and a faster moving one for those continuing their journey. This likely added unnecessary complexity.

For Indian cities, the simpler airport design where walkways run for about 100 m and then terminate on hard ground (for those wanting to get off to get to nearby gates) and resumption of the walkway about 10 m further on for those continuing to more distant gates seems appropriate. This could be adopted with a bus stop design heuristic, where the hard ground termination – or travelator stations – could happen every few hundred meters (with visual and audio announcements) and leading, on both sides, to escalators/elevators that take passengers down to each side of the street.

These stations, in turn, could be integrated with bus stops and metro stations to maximise public transit efficiency and use for longer distance commuting.

What would such a system cost?

If the Metrino is expected to cost Rs 50 crore per kilometre with its advanced driverless transportation systems for safety, monitoring and intelligent management, the simple airport-style travelator as an urban transit alternative could possibly be one-tenth per kilometre.

The re-design along the lines described above may double the cost per kilometre, say, Rs 10 per km, which would still be an extraordinarily inexpensive solution to move 10,000 people per hour in any neighbourhood area that otherwise would require relatively expensive metro, bus or taxi services.

As a comparison, an air conditioned bus, such as a Volvo that is now a common sight in the big Indian cities, costs about Rs 1 crore each and can transport about 80 people when full, including standees (most of them run at 50 per cent capacity). Meaning you would need 100 such buses costing Rs 100 crore to transport the number of people a travelator could for a fraction of the cost.

Of course, the buses go longer distances but have the impact on traffic congestion, the cost of fossil fuel and pollution from emissions – all of which could be an advantage when you consider that a travelator would run on electricity and will likely cost much less per person.

Benefits

There are many benefits from seeking to build an extensive WalkTransit system in India’s cities and towns:

Cost

At Rs 10 per kilometre, WalkTransit infrastructure could cover 100 km for just Rs 1,000 crore. Any public transit system can’t beat that number. This would seek to serve neighbourhoods and, therefore, de-congest main streets.

Volume

At least 10,000 people per hour in both directions at any locality.

Ticketless

Municipalities could make this system free to use and recoup the much lower cost of maintenance in other ways. Ticketless travel would encourage greater use.

Revenue possibilities

Municipalities could earn incomes from kiosk rentals at stations and vinyl wrap advertising on the glass enclosure that would be visible on the outside while shielding those on the inside from sunlight, while also allowing them to look outside. WalkTransit stations could have small local businesses such as cafes, newspaper vendors, mobile stores and florists.

Changing public behaviour

By making the system free and providing air conditioned comfort with reasonable speeds (up to 5 km per hour), it could encourage more people to use it and, thereby, also be prompted to walk on the travelator. Such walking would contribute to better public health and help halt the increasing instances of chronic disease owing to sedentary lifestyles. If a WalkTransit system felt pleasant to use, people might actually use them and make gradual behavioural changes for their own health benefit.

Self-powered for auxiliary use

Solar panels on top of the glass enclosure could power local requirements such as LED lighting, audio-visual displays and CCTV. Power for the motors to run the travelator could come from the grid.

Higher involvement in local community and commerce

Numerous studies have shown that more involved communities tend to be safer and better overall. WalkTransit could encourage more local people to use the system instead of “app taxis”, afford slower vistas of the surrounding areas from a height, ability to have leisurely conversations with “co-passengers” and help local commerce.

Superior solution to expand across smaller cities

WalkTransit offers an incredibly inexpensive solution for smaller Tier 1 and 2 cities that have inefficient bus services and cannot afford metros.

Push to Make in India

Finally, this could propel “Make in India” forward. The technology is stable and known, no transfer of technology required, and only companies manufacturing domestically could be qualified to tender.

Re-defining public transportation for the cities

The most important benefit is likely in the long term and largely inestimable. Indian cities have become notoriously difficult for people to walk in and navigate owing to the poor quality of sidewalks, chaotic traffic, high rate of accidents and extreme pollution. People have stopped walking, and only a few do so in parks. More and more people now use motorised personal transport, which only adds to the congestion. The other big benefit is its low power consumption and zero pollution.

Medellin’s example

Can we re-define public transport that could be embraced by other cities around the world for its innovative thinking? The question is worth asking because of the possibilities that it holds.

In 2013, Medellin in Columbia, one of the world’s most violent cities, was voted the most “innovative city of the year” by the Wall Street Journal. It beat New York City and Tel Aviv for first place. There were many reasons for conferring the honour upon that place – among them mobility, buildings and spaces, and participatory citizen budgeting.

But one of the most talked about changes to its cityscape was the deployment of a large outdoor escalator system in 2011 that connected poverty-stricken slum neighbourhoods along the hillsides to the prosperous valley floor and integrated an otherwise separated city.

Slum-dwellers could access job opportunities that were out of bounds because of distance.

Other out-of-the-box transport systems in that city included a free, public bicycle system and a much-acclaimed bus rapid transit system. The much-preferred and oft-touted word in India today is “inclusiveness” and what better example of this than Medellin’s?

WalkTransit could well be an extensive, safe and innovative public transport system for every neighbourhood in the cities. It represents an opportunity for the Indian government to think radically and set in motion a disruptive, collaborative, public-private partnership involving licensed operators for specific areas in each city, government-owned infrastructure that operators would use, technology companies to provide intelligent systems, ticketless use to encourage users to give up or leverage traditional transit, coupons tied to mobile apps which, say, monitor health while using the travelators and offer lower health premiums or doctor consultations, an efficient and effective transit authority, and much more.

We are only limited by the scale of our imagination.